.

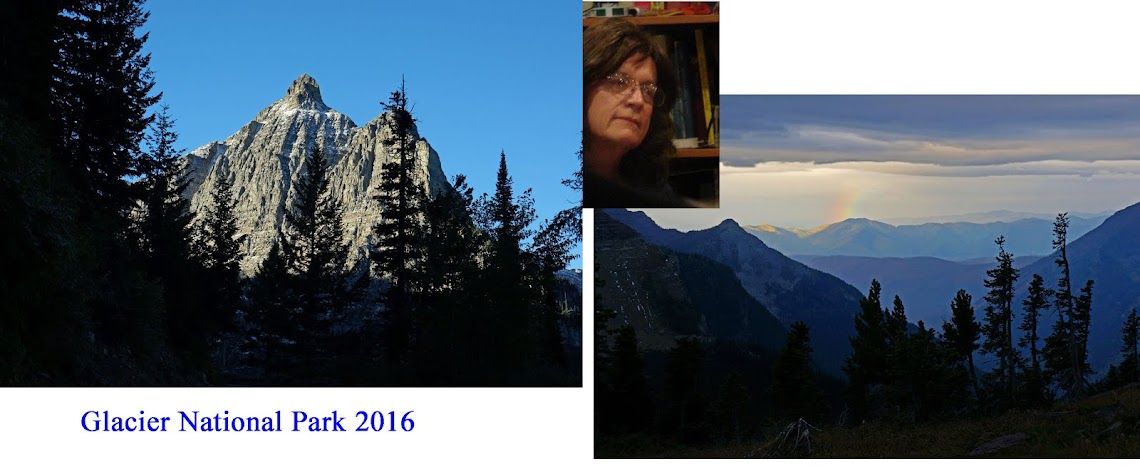

From the peaceful shore of

Josephine Lake, looking up at Mount Gould in early morning, with just a

sprinkling of snow from yesterday’s little storm, it’s hard to believe that

such sprinklings carved out this entire valley.

Harder to believe is that some of the rock high on this valley wall was once one-celled creatures, living in cities called Stromatolites over a billion years ago. Individuals, called Cyanobacteria, built cabbage-like groupings, which, when cut by glaciers, look like tree rings. See their traces preserved here in hard rock as fossils.

It has been so windy and stormy the last few days that any lake

I saw has looked rough as a miniature North Atlantic Ocean in mid-winter. But not today. This small pond, beside Josephine Lake,

carved by the same glacier that carved the larger lake, a replica of that lake,

imitates the larger lake it represents.

It reflects, in a small way, some of the trees that Josephine Lake

reflects. And when we see the

insignificant pond from a different perspective, it reflects a morning cloud

from high above both it and us.

It has been so windy and stormy the last few days that any lake

I saw has looked rough as a miniature North Atlantic Ocean in mid-winter. But not today. This small pond, beside Josephine Lake,

carved by the same glacier that carved the larger lake, a replica of that lake,

imitates the larger lake it represents.

It reflects, in a small way, some of the trees that Josephine Lake

reflects. And when we see the

insignificant pond from a different perspective, it reflects a morning cloud

from high above both it and us.

As we climb up the valley, and the sun climbs up the sky, Mount

Gould speaks more loudly and clearly, telling us of its past: “Though my rock is very old, the surfaces you

see were hidden until just yesterday in my time, a mere 20,000 years ago.” That’s when the glacier that sculpted Mount Gould began

to melt, the glacier we are on our way to see.

As we climb up the valley, and the sun climbs up the sky, Mount

Gould speaks more loudly and clearly, telling us of its past: “Though my rock is very old, the surfaces you

see were hidden until just yesterday in my time, a mere 20,000 years ago.” That’s when the glacier that sculpted Mount Gould began

to melt, the glacier we are on our way to see.

Below Mount Gould, we see what looks like a snowfield with a

shiny spot at its center. The map calls

it Salamander Glacier, and it’s hard to imagine so small a river of ice carving

anything, much less this entire valley.

Below Mount Gould, we see what looks like a snowfield with a

shiny spot at its center. The map calls

it Salamander Glacier, and it’s hard to imagine so small a river of ice carving

anything, much less this entire valley.  |

| Big Horn Sheep |

|

| Mountain Goat |

|

| Moraine of debris left by a glacier |

Unlike the sure-footed sheep and goats, we need a trail to get around this cliff-face and onto the moraine leading to the glacier.

Standing on the terminal moraine, we see three glaciers and a

lake—Salamander Glacier on the right, Grinnel Glacier below it on the left, and

a small unnamed glacier on the upper left.

Below them is Upper Grinnel Lake.

You might ask why we call them glaciers; they look too small to carve

anything. It’s a fair question and begs

a definition of “glacier” verses “snowfield.”

A “glacier” is thick enough to compress snow into ice, and it is heavy

enough to slide slowly down a valley.

These three qualify, but just barely.

Let’s look closely at them.

Standing on the terminal moraine, we see three glaciers and a

lake—Salamander Glacier on the right, Grinnel Glacier below it on the left, and

a small unnamed glacier on the upper left.

Below them is Upper Grinnel Lake.

You might ask why we call them glaciers; they look too small to carve

anything. It’s a fair question and begs

a definition of “glacier” verses “snowfield.”

A “glacier” is thick enough to compress snow into ice, and it is heavy

enough to slide slowly down a valley.

These three qualify, but just barely.

Let’s look closely at them.

Salamander Glacier has solid ice, as seen where the snow has

melted or slid off its surface, revealing layers of its icy past as it slid

down this steep valley. It is still

moving as shown in aerial photos taken each year. But its life as a glacier will end in just a

few years unless something changes. Estimates are that all of the glaciers in

Glacier National Park will be gone by 2030.

Salamander Glacier has solid ice, as seen where the snow has

melted or slid off its surface, revealing layers of its icy past as it slid

down this steep valley. It is still

moving as shown in aerial photos taken each year. But its life as a glacier will end in just a

few years unless something changes. Estimates are that all of the glaciers in

Glacier National Park will be gone by 2030.

Grinnel Glacier lies on the shore of Grinnel Lake and below Mount Gould, which we have seen all the way, hiking up this long valley. It reminds of the tidewater glaciers we saw earlier on this blog in Alaska, in this “Rivers of Ice” adventure. Pieces of it break off and float away into Grinnel Lake.

Why are rocks and gravel riding on top of Grinnel Glacier? It’s because the glacier is melting. Material it carved from the valley above, perhaps a thousand years ago is left on top as the last of its ice melts. This glacier is now too small to do any more sculpting of valleys.